This is the fourth exercise book by Albert Baker and stands apart from the others as an account of Albert’s time in the Dover Borough Police Force. Page numbers from the notebook are included in square brackets. Some quotation marks are have been interpreted as parentheses, and paragraphs have been added for easier reading; in addition single quotation marks have been added to distinguish speech where the original lacked them.

[page I]

Dedicated to my three children Gilbert Cecil, Dorothea Lydia Tapley and Albert Edward

This book is really meant as a review of the Dover Borough Police as I knew it up to 1920 and before the KCC [Kent County Council] absorbed it with all Boroughs and Cities in Kent.

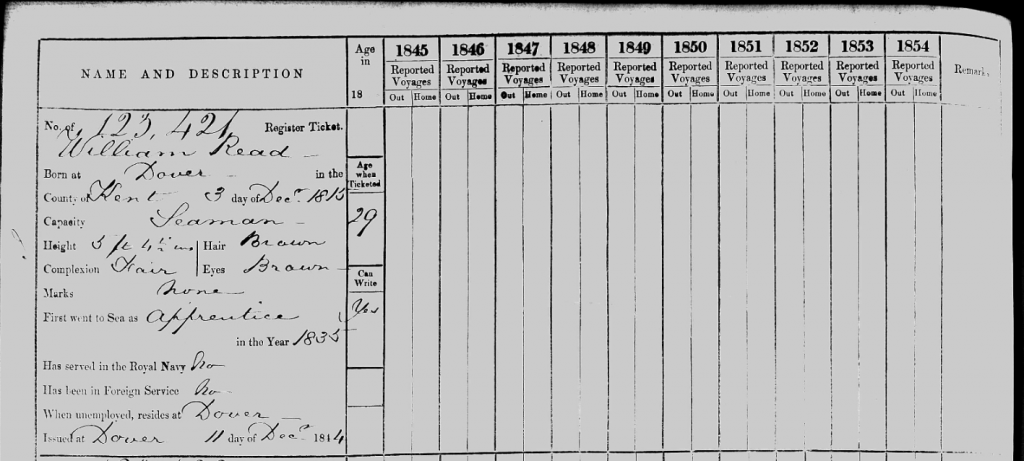

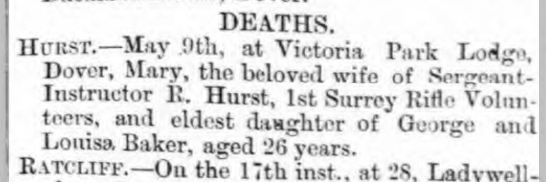

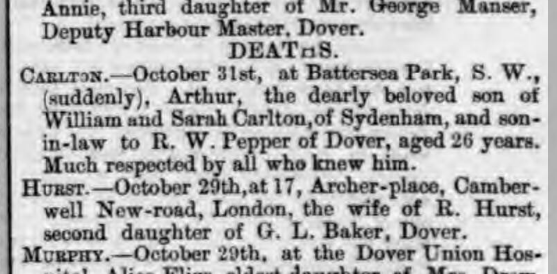

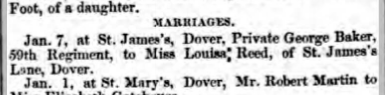

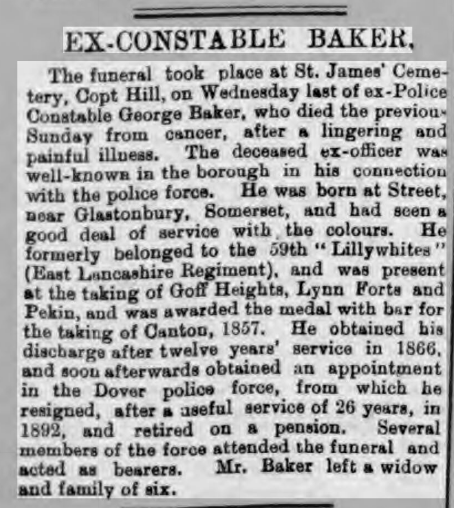

My father, George Baker, a native of Street, Nr Glastonbury, Somerset, enlisted at Wells, Somerset for the Crimea War or Mutiny, or one of many Wars going on but as he was too young and did not look strong and healthy, he was sent Via the Cape (as there was no Suez Canal) to China and after about four months landed there; there had been “Cholera” aboard on the voyage and the number to land was greatly reduced by it. Soon they were marching towards Canton and he was at the taking of Canton and Taku Forts in 1857 and was the only man in Dover to wear a medal for it. When the regiment returned he met my mother in Dover, Louisa Read, a Dovorian, whose mother’s maiden name was Greenward, and later they were married.

Then the regiment was ordered to India, and my mother being on the strength of the regiment went also, the same route Via the Cape. It was a very bad passage out, and many of the soldiers wives were in Sick Bay. They were at one time battened down below hatches owing to storms.

My father had enlisted in the “Pompadours” or the Lilywhites”, Lancashire Fusiliers his elder brother had also enlisted and was in one of the above mentioned regiments but I don’t know if that is the right order, or Vice-Versa. Anyway his brother claimed him to his regiment and they marched together up country in India, the women being conveyed on Bullock Carts. In the hot season they could not get away to the hills and my mother had sunstroke, she was to be invalided home, so father as his period of service was near its end requested his discharge and would not consider extending his service as he had arranged to do. They were both returned home and father got his discharge and came to Dover. [page II]

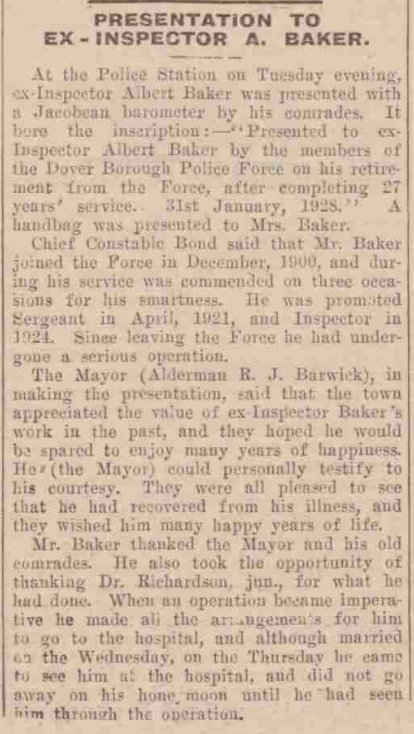

His first task was to get a house and then employment. The Upper and Lower Lodges of Victoria Park were empty so he went to see the owner Mr Sheriker Finnis who rather wanted him to take the Lower Lodge but father wanted and had the Upper Lodge. He was told about a job in the Police Force and applied for and got it. I think he said his wages were £1 per week less a halfpenny owing to stoppages for superannuation. Mr Finnis was glad as he said now a PC was there it would safeguard the property, as he owned most of it and he would charge father 1/- [a shilling] per year rent, and when he went to pay it, it was always handed back and a sovereign with it. He was appointed on Probation 24th April 1866 and superannuated 28th June 1892. I was appointed on Probation 18th December 1900, Superannuated 31st January 1928.

Of course the Lodge at that time had no sewage or water services, father had to open a man-hole cover near the front door of No1 Victoria Park and draw two or three buckets of water from a tap at the time. There was no cesspool, only a pit that would be emptied at night at intervals I remember one night the men must have got drunk, father was on duty, when they started to take the cart away the tailboard fell out and they were there for hours clearing up before broad daylight. Later on water was laid on and drainage and we were charged 2/- per week as it had cost such a lot to make the connections. I think it was paid through Stilwell and Harby. Father always said “Don’t join the Police, you would be too quick tempered”, and said the injuries he had received in Bridge Street from Charlton Roughs when making an arrest of one of their number was at the bottom of his trouble. He was always more or less in pain and died of Cancer of the Stomach [page III] 16th July 1898, after over 32 years tenancy.

Almost before he was out of the house Major De Moleyns from No 9 called and told mother the Park Committee had given him a distasteful job, it was to tell her they wanted vacant possession of the Lodge in six weeks as it was a police house and two policemen were after it. As Mr Finnis was dead there was no appeal to him, the committee apparently running the place. It never was, or has been a Police House. I went and saw the Mayor also Mr Stilwell who seemed the one most concerned and told them I would at the first opportunity make application to join the Force, but they would not hear of it, or consider my appeal, it seemed to mother to be the end of things to lose father and get turned out. Anyway, she had to go and Groombridge moved in, I am in a way sorry: but they did not seem to have the best of Health and neither made old bones.

Some years later in Cannon St I met Mr Harby and Mr Hugh Leney (what he had to do with it I don’t know) they stopped me and said ‘Hello, Baker, we were wanting to see you. The little cottage at the Park is empty and it would suit you and your wife. What about it, you lived there quite a long time.’ I was in uniform and how to keep my temper I didn’t know. ‘Come Come’ said one of them ‘we thought you would jump at it.’ I replied:- ‘No Sir, you turned my mother out but you won’t turn my wife out.’ They seemed flabbergasted and said “very well” and hurried off. I thought perhaps they would get at me somehow but perhaps they thought I was right.

In March 1900 I made application to join the Force, two candidates being required. I spoke to a Mr Bond (later a brother-in-law) who at that time was I believe thinking of joining the Metropolitan Police, and we both make [sic] application. There were many [page IV] applicants, I was in the short list of six interviewed the second time then Bond, Turner, Dane and Sutton, (four instead of two were appointed) and I thought that’s it. Sutton was a very big ungainly but powerful man, he soon got reprimanded as it was known instead of going to bed to rest he was spending all his time in the U Farm[?] Greyhound and after about seven or eight months he was got rid of. I knew nothing about it but met Mr Knott, Inspector, in the street. I think it was the first time ever I spoke to him. He stopped me and said: ‘Are you still desirous of joining the Police’, and I told him I thought my employer, A Leney, to whom I had to apply for a character and who had tried to put me off from applying (saying I suited them admirably and they hoped I would think it over, but gave me the character) had had something to do with me being passed over. He said never mind that now, you are helping keep your mother and should have filled one of these vacancies. If you care to be at the Town Hall at 2.0pm Watch Committee and then pass the Doctor you will have the position.

I never told Leneys, got all I could out of cellars and despatched them to the loading floor for the afternoon and when I went to dinner changed and dodged my way so as not to be seen by any of Leney’s employees to the Town Hall, went before the Committee and was appointed subject to medical examination. I was taken by Sergeant Lockwood to Dr Ormoby, Police Surgeon, Effingham Crescent and passed as fit. When I got back to the Police Station there stood Mr J Saunders, Superintendent leaning on his stick. I admit I felt a bit over-awed at the way he looked at me, I expect he thought what a change after Sutton, and then he said Well: I’ll make a man of you if you don’t make a fool [page V] of yourself. He asked when I could make a start and I said I should like to be fair to Leneys and give a full weeks notice and help them with the xmas rush although most of the Ales were already in their various cellars. He said report here after seeing Mr Leney.

I went home and changed and got back somewhere about four o’clock; when I showed up in the brewery Mr Marsh the Foreman was furious, he had sent for me, and got no answer twice, what was I thinking about. I should be sacked for it etc etc he would let Mr Alfred know I was back. I told him I was handing in my notice. Whatever for he said, and I told him I wanted to see Mr Alfred as soon as possible, within a minute or so I was sent for to Castle Street Offices. There was Alfred, Hugh and Frank to hold the enquiry. When asked to explain the matter, I tendered my notice, that rather nettled them until I told them I had joined the Police, then they congratulated me and said why didn’t you let us know we could have made arrangements for you to have time off, and I reminded them I did that before and was not successful. They said if I would get as much of the Xmas beers out as possible, they would not hold me after that week so that I could be free as soon as possible, also they would like an extra thorough stocktaking for the benefit of my successor, which I did the following Saturday afternoon to bring everything up close.

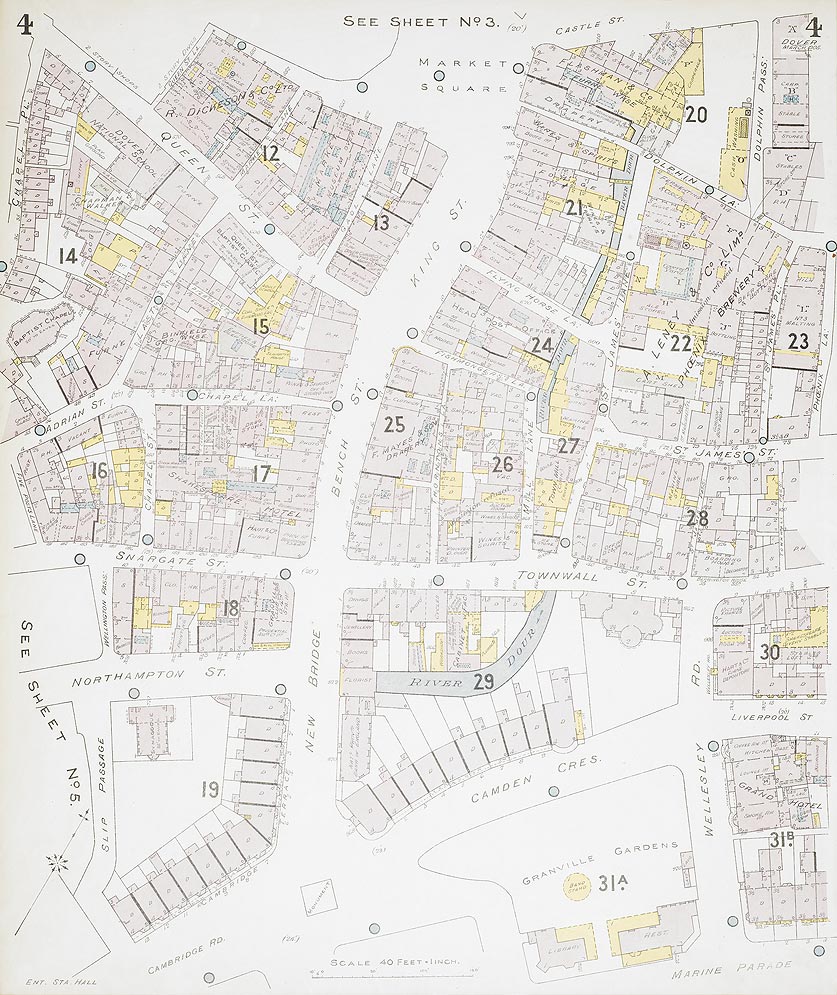

I called and told the Sergeant at the station and I was told when to attend to get my clothes. I had to go to Jarrets to get fixed up, but it was a most tricky job as Sutton was twice as big as me, I could do nothing with his clothes, he had an extra big belt so I was served out with a very old one [page VI] that someone had apparently had had all their service, the metal all brass “no plating on it” and the leather dull and chipped. For night duty I had to fit the clothes, not them fit me and the helmet I had to pack with paper folded four or five times to keep it off my ears, but trousers were the trouble as all the reasonably sized ones had been shared out between the four recruits in March. I went down to the secondhand shop in Snargate St that sold ex-Metropolitan Police Trousers at 2/- per pair and bought my own trousers. What a job getting rigged up for duty that night, I started on the job early and got Mum to pleat the back in folds till I could get the belt round, then the job was to pull my lamp to the front owing to the pleats and get my truncheon out of, or into, my tail pocket, it was bad enough to do it if the clothes fitted but as I was it was almost impossible. The first time on parade my pocket had to be found for me and it was a nuisance for a very long time, especially in the Summer as topcoats had to be worn at night, no matter how hot the weather.

I was shown round two or three beats a night, and by the time came to leave at 6am I was done up as each man showing me round had to take me to every nook and corner which did not please them, even though I told them I knew all the places. About the third evening I was with PC Frank Company in Priory Road as the Pubs were turning out. He had occasion to speak to three young chaps who were drunk, one of them with a thick piece, or stalk, of seaweed. He struck at [page VII] Company and in a tussle Company fell or was knocked down. As I thought the prisoner whom I had arrested would be rescued I ran him to the Police Station and luckily got him in the door, the man who was supposed to be standing there arriving from inside at that moment. I handed prisoner over and went out and met Company hobbling along, the other two men had gone. I don’t remember what happened to them but I had to attend Court in my Fred Karno’s [Circus] uniform, to my disgust.

Another night I was with George Finch to be shown round what was known as No 4 (lower part of Waterloo Crescent from the Grosvenor [?] Gardens or Monument to North Pier) we had to be on Commercial Quay at 11.0 pm “turn out time” and remain till things got quiet, it was always a nuisance with sailors and troops and women seldom a night without trouble and frequently 7-8 policemen there, as well as military police. When we got back to the Esplanade Hotel, Mr Cessford, Proprietor was outside and asked if we would take any refreshment. George did not reply so I said “Yes” George turned on me and said you must not drink on duty and sent me to try the Wharfingers Office and other places, when I returned Mr Cessford was waiting with a drink for me, George had had his and was on the Sea Front. We went down the North Pier and he lit up his pipe and I a cigarette, he told me I was not allowed to smoke on duty so I drew it lightly and on getting to the opening near the Monument, pinched the end out as I could see Inspector Nash at Page’s corner near Harts Furniture shop, standing in the doorway. George said I was mistaken and we started to go to the top of Snargate Street. As we got to the Monument he then saw it was Inspector Nash (Johnny we all called him) and knocked his pipe on the railings [page VIII] causing sparks to fly all over the place. When we met, George said ‘All right Sir’ and I followed suit. He replied ‘All Right, but there’s no need to make fireworks of it, is there’. Some spoke hardly of Johnny but I had no cause to, if you did as he told you, you could not be very far wrong, in fact I liked him, like others he had his funny little ways but haven’t we all. I always said “If you can’t please ‘em, don’t tease ‘em”. He was about 1903 killed in assisting to launch the lifeboat from North Wall way.

It was usual for a recruit to have months of night duty, anything over three months according as to how they were shaping, but I was out for Evening and Day duty at about nine weeks. I did not feel self-conscious or strange at all having been more or less a member of the force all my life.

Conditions of service then were: Eight hours of continuous duty seven days a week, Five days Annual Leave and one day on leave a month “to be drawn for” making it possible to draw the first day of January and the last day of February, and so if on night duty doing about 60 days, going on in the dark, coming off in the dark and going to bed and getting up in the dark. It was the rule to do eight weeks night to four weeks day, the night period to include Evening Duty one week 6pm-2am. I don’t know any man that liked night duty except myself, I revelled in it but must admit sometimes in the bitter cold I would have liked to be in bed, it seemed that you had got it all and no one to share it, fingers numb as you held your food to eat as you walked and tired arms with trying to get your tea bottle warm over a street lamp. One place I tried was standing on a short pillar of the wall of New St James [page IX] Church, next to Harold Cottage, but I also used to try and warm it at a banked fire at a Nursery and sometimes at a bakehouse. It was arranged where a man’s beat touched the station that he would carry another mans can to him after warming it up at the station but it was never a success with only one small gas ring and so many wanting to use it, by the time the man received it, it was almost cold. We had a can advertised at 2/9 each to light up and leave in a doorway, it burned methylated spirit and had two tubes for the heat to pass through, frequently you found it cold, the wind having blown it out, it was not a success.

We started pay at 24/4 ½ clear a week, after 18 months “if service satisfactory” 26/9 ¾, another 18 months then 29/8 ¾ then five years “to get 8 years service” to get top price 31/2 ½ per week. Later there came a scheme to increase our pay, after I think 15 years it was called Badge Money and we wore a silver chevron “inverted” on the sleeve that gave us either 1d or 2d per day, I cannot be sure which, then at 22 years another badge and another 1d or 2d, that was as far as a constable could get.

On pay day “usually a Wednesday” I or someone else would be handed 1/- or 1/6 and told to get the equivalent in farthings and would go to small sweet shops, perhaps several before we could get enough so that the pay could be handed out correct. We paid a small sum for old clothes instead of handing them in, and that would be stopped at so much a week, we also received 1/- per week boot money paid quarterly. There was one tour of duty which was imposition, but as soon as N. K. Knott was Chief he altered it. A man changing from day to night duty would parade for [page X] night duty the same night till 4am. It was altered so that a man coming off at 2.0 pm on Sunday did not parade again till 10.0pm Monday. There was no time off for Court and after being night duty would be at the station at 10:45am and perhaps remain nearly all day over a simple case because other cases were more important and then night duty again with hardly any sleep, and all meals upset. No overtime and none expected . The old policeman might grumble but if he was on a job where he could not finish it up in time, he had a certain amount of pride and would resent having to hand over to someone else. The constable was always at a disadvantage with their Sergeant especially at night, then he had what was called a beat-card for the ground allotted to it and the time allowed to work it, all on foot, and perhaps quite a lot of unoccupied premises, schools, churches etc that had to be frequently visited, and always on the first and last round of the beat so as to take over correct and hand over correct, or at least as correct as you could.

Fancy, from the Engineer PH to the Borough Boundary beyond the Hare and Hounds, to Tapley Farms Elms Vale Road, Halfway round Fan Hedge, Winchelsea, all Maxton and Clarendon Street and Place every 50 minutes. You would have to hurry to go to the end and back without stopping for anything. I was always a quick walker and one night after seeing the Orange Tree, Crown and Sceptre and Grapes PH out I arrived back at the Engineer PH at 11:20pm. I am telling you this to show how a Sergeant could harass a man for nothing and threaten to report him for failing to touch a certain part [page XI] of his beat in the time allotted without some reasonable excuse. When I got back there was the most detested Sergeant on the Force (who was in charge of the upper section), waiting for me. I reported “All Right, Sergt”, then he flew all to pieces. ‘Where have you been, What time was you here last.’ I was very surprised to see him as if he had been doing as he should, to see all the upper section men before midnight so as to give all men a chance to see their unoccupied places he should have been somewhere in Buckland so by neglecting them he was throwing them all out of their working, as some of their beats laid wide from the main, on purpose to harass me. I had never given him or any other Sergt cause to complain for being slow. I told him I had not been there since I came on, and had seen the PHs out on my way back. He stormed, called for my beat-card, pointed out I was allowed 50 minutes. I told him, and he knew, that was impossible even if I ran, then he went off muttering loudly about 50 minutes, that done it. I went up round Clarendon to the Horse Trough, Elms Vale Road back to Winchelsea and neglected to go out further so as to be back at the 50 minutes. I did not see him till I turned the corner of the Engineer and there he stood. I reported to him and cleared out but again never went beyond the Horse Trough, it was impossible. I kept my light off the houses and sidled down on the left hand side keeping in the shadow as much as possible but he was not waiting there for me. Then the thought came, suppose he has gone to Maxton or Elms Vale to wait, he seems bent on having me. I waited under the light for about 5 minutes then started up Malvern Hill, but after a few steps returned and saw [page XII] him come from Clarendon Road under the lamp next to Priory Bridge and go towards the town.

Years later after he had retired and was caretaker of the empty Dover Castle Hotel, Clarence Street, I had occasion to call the attention of the Landlord of the Rose and Crown PH to the fact that it was after time and told him to clear his house immediately. He was surprised and said so, I said if he did not comply at once I should add that to a report I was going to submit to the C. C. About the last to leave was the former Sergt who had been a teetotaller for the latter part of his service. He gave me a nice pleasant sneer and cleared off. I told George Finch my Sergt all about it and he said:- ‘Wait and see what happens tomorrow. I’ll be here myself so as, if necessary to corroborate’. The following night, I stood immediately opposite the door. Someone looked out and turned back saying ‘Yes, here the — is, waiting for us’. The Sergt had not turned up. Out they all came and the bar door was bolted. I had not heard the side door bolted and was sure there was someone there and stepped into the opening just as the ex Sergt came out, what he called me and mine settled it, sack me or no, I was going to settle things, my lamp and belt went on the ground, my tunic was all but undone to the neck when someone grabbed me from behind. George Finch, he said you damned young fool, he’s not worth it, just put yourself straight and come along with me. I never heard anything more about it. Perhaps old George did me a good turn but that ex-Sergt whenever he saw me afterwards would cross the [page XIII] road or get out of my way somehow. He never ought to have been a Constable. He’s dead now, but has relatives still here.

Another time another Sergt Hughes upset [?] me. I was morning duty and got to the Station at 5:45 just as he had shouted out “Fall In” so as I went in I shut the door and latched it. I was really the first on Parade as I knew I was going to Buckland so put my cape and bottle on the bench. After he had inspected us and read out the informations we got the “Quick March” and went off to take up our Beats. I saw him about 7.45 am at Beaconsfield Avenue and he said: ‘Be prepared to be at the Chiefs Office at 9 am, you had better ring in about 8.40 or so’. I said ‘All right Sergt, whats up?’ ‘Oh, don’t you know, I’ve reported you for parading late for Duty this morning’, but I said ‘Sergt I was not late, I closed the door when you called Fall In and was the first on Parade, why didn’t you challenge me then if you thought I was late not leave it till now, as I cannot call the others to speak for me’, he replied:- ‘No you can’t I have spoken to them’. I rang down about 8.45am and enquired, and was told to be there at 9am. When I was called to the Chiefs office I felt mad as I was quite innocent, and there being no “Constables Branch Board” in those days I knew I was for it as the Sergt had got his talk in first. The Chief said: what excuse have you got to make, you have heard what the Sergt says. ‘What have you to say?’ I replied:- ‘What’s the use of me saying anything, you’re bound to accept what he says [page XIV] as I can’t call any witnesses, he has so he says seen them all’. That upset the Chief, said he had never heard such insolence and ordered me to get out. He had the supposed offence (the only one I believe during my service) recorded against me and although I had commendations that did not wipe out my heinous offence as if the records are still preserved can be seen still.

Not long after this same Sergt was found sitting on a dwarf wall in Park St in the early hours of the morning so drunk, he could not stand on his feet so was helped by PCs to a Doctor who sobered him up. If I had found him I should have let him take his chance, not taken him to the Doctors. I never again helped him to make his written reports as I had done before. He was a useless sort of a fellow and frequently had a lady friend with him when on duty, he had a good wife at home.

I was a strong young man having been used to barrelage at the Brewery and did not fear for myself, in fact I never considered fear of any sort, but in the early part of 1901 I had I think the toughest job of my life. I was one morning about 11am in Strand Street watching some colliers being discharged when the landlord of the George Hotel, opposite the Prince Imperial called to me from the steps at the entrance in Strand Street saying he had two navvies in his house drunk and he wanted them ejected. I went in after telling him he must ask them to leave in my presence and if they refused, to make to put them out and call me for assistance [page XV] he asked them to leave but until I spoke and told them to go they sat still. When I went towards them one got up and went out but I had to speak several times to the other who when he got up surprised me, he was a giant of a man. I advised them both to go to their barracks at the Oil Mill which were being used to accommodate them as people would not have them as lodgers, they were Irish and came in hundreds by ship to work on the cliffs and at the making of the Dockyard, East Cliff. They wore knickerbockers and blue puttees, were very broad in the shoulder and narrow at the hips, they drank porter till it was said it ran out of their eyes.

These two then said they would go where they liked and went into Snargate St. A Sergt came down saying he heard it looked like trouble on the Quay but said he could see nothing out of the ordinary, he never did. I showed him the two men but he never even spoke to them and cleared off. He never had much heart for a row, but had plenty to say, and would drink his full share, if there was anything doing he was conspicuous by his absence. He had not been gone a minute before they made for the Scotch House, back of the Harp Hotel, next to Trinity Church. I knew there was only a barmaid there so stepped down into the Bar and waited for the attendant and told the girl not to serve them and to ask them to leave. I would wait at the door as I did not want a rough house a few feet below road level; out they came and I again advised them to go to barracks and the smaller one did so, but the big fellow bawled out, ‘You’ve stopped our Porther’ [page XVI] and started creating a disturbance threatening what he would do with me, and he certainly looked as if he could. I did think it would be nice to have a mate but I told him if he did not follow his pals example I should have to lock him up. Oh dear, he shouted ‘who will you get to help you’ and I replied I should want no help. That riled him up and as he looked down at me, he started swinging his arms about showing me what he would do with me. He was much over 6ft, at last I collared him but had to reach up to do it, when we got to the George his pal turned up again and he wanted to go on to Commercial Quay, but I said ‘No, if you could not go your way you will come mine’. With that he put his long arm across and pushed against my windpipe with all his power, he did not try to squeeze it and I let my head fall over to the right but he still kept the pressure up till I could see lights and dots and knew I should go down, so forgetting all about Queen Victoria I made a quick upper cut and down he came with me sticking to him like a leech so that he could not get a blow in.

We rolled up Snargate St, his mate and others saying ‘One dog, one bone, let them be’, no-one came to my assistance, I think everyone was afraid of the uncouth navvies. I know it hardly sounds believable today but I don’t remember being on my legs until I got to slip passage. He had snatched and thrown away my whistle, my helmet was gone, smashed up, my new tunic [page XVII] and a new belt I had just had issued to me was smothered in tar as the road outside Jarretts had just been repaired. Every time I came underneath in rolling up Snargate Street, he caught hold of my hair and tried to slam my head into the ground until at last I was nearly exhausted by putting all my strength into my neck and shoulders to keep my head up. As it did not seem any help would arrive I told him if he did that again I would do the same to him, he had also tried to crush my lower ribs which were painful for weeks afterwards. When we got to the Standard Office I could put up with no more so as he came underneath I took his hair and banged his head on the edge of the kerb. He went flat out, and I got my handcuffs out and put one on, it nipped his wrist as he was so big boned and then I drew the other near and had rather a difficulty as that wrist seemed even bigger than the other but I forced it to shut, the pain must have restored him to consciousness and as soon as he realised he was cuffed he snarled and brought his wrists down on the kerb with all his might and the cuffs broke. The only pair I have ever heard of being broken apart. He still had one on each wrist as it had broken near the chain, and then the fun started all over again.

I forgot I was a policeman “and even if I got the sack” I remembered my father had been injured so severely it was held to be the cause of his death. What [page XVIII] happened from there to slip passage I don’t know but I do know outside the Express Office someone saying:- ‘Do you want any help Bert’ (I always thought it was Charlie Cole from the Packet Yard but he always denied all knowledge of it). At the time I was top dog and keeping his shoulders down but it was not easy. I said ‘feel in my back tunic pocket for my dog-line, make a running noose with its brass eye and get it over his feet and lash his legs together’, others came to help then and I sent to Gaol Lane for a wheeled litter and instructed them how to unship it and to pass a strap round each leg before buckling to the sides. When after fastening his arms we lifted it up we had a job to strap his wrists, even then he tried to get away and then I saw one of the leg straps had not been passed round the leg, he soon found he could draw one leg partly up and did so, and shot it down again, he had a worn heel-tip and it cut the canvas so one leg was hanging in the hole supported by his other leg, When we got to the “Fountain”, Market Square, now the Westminster Bank, PC Cooney was outside the Duchess of Kent PH and came over. He wore a beard and prisoner on seeing him said ‘What have you got… old father to help you’. Cooney thinking to stop his language went to put his hand over his mouth and was lucky he was not badly bitten as prisoner tried to get his teeth into him but his hand was withdrawn just in time. I had to go at once to get my tunic opened [page XIX] up for new quarters to be inserted. Next morning Inspector Nash talked about putting me on report for not charging him with assault, I said “Sorry Sir” but look at him and look at me, he looks like the assaulted one, he said. ‘Rubbish, if you knew what folks have told me that saw it you don’t want to pity him I shall mention it to the Magistrates’. Matthew Pepper sent him to Canterbury.

When I was going to the Magistrates Office some time later I saw him with others lining the kerb outside the International [word?] Market Square, could not miss him owing to his size. I did not think about when he would be leaving prison but you could not mistake him, he towered above all the rest. When he saw me he started walking with slow but long strides towards Flashmans, and when I knew he was close behind I turned and faced him. He put out his hand and said “Will ye shake hands Sor”. I was thinking he might grip my hand and strike at the same time but I said “Certainly I will” and shook hands with him. He expressed his sorrow but said it was me being so small that had annoyed him most, and added ‘you’re the finest policeman I ever knew. If it had taken six of ye I would not have minded’. I let him know I had let him off lightly, but I knew different, it could easily have been a bad job for me. He said ‘if ever you’re in trouble and Patsy’s about he’s wid ye’, he told O’Leary [rather?] a big fellow and I never had trouble with any of them after. If there was likely to be a disturbance I would look round and if he or [page XX] O’Leary were about would give them the nod and they would clear them out with their elbows. I had a new pair of handcuffs that I carried for the rest of my service, they had four locks and would fit the smallest or largest wrist. I know some who would have liked them but they were never taken from me and I handed them to my successor.

The Dover Observer had an article, (their office was next to the Masonic Hall), why didn’t they telephone for assistance not publish it afterwards. I have the cutting from their paper. I was living over a Jewellers at 167 Snargate St at the time and my wife saw me rolling in the crowd from the window but could not recognise who it was, she thought it was perhaps a couple of drunks. When I got home I said this job might be alright but you don’t half earn your money. I have had other rough houses but that was the worst, and in broad daylight I could not use any means to protect myself, whilst he could use all and any means against me.

Then came the death of Queen Victoria and we were re-sworn under King Edward VII. Helmet plates and buttons were altered to show a King’s crown. I still have an old helmet plate and I think a few buttons, the buttons then were not chromium plated but real silver plated.

The Boer War was over, troops coming back and everything seemed fine. Our duties were carried out as usual. There were lots of things we did that they would not do today. One thing I did not agree with was becoming an electric light extinguisher. As daylight came in you would switch [page XXI] off public lamps in Harold Terrace, Maison Dieu Road etc etc. As it got near 6am you had to hurry up to leave duty on time, and as it got light during the winter months say at 7 oclock or so, the 1st relief man would have to do it. What opportunities for a wrong un if he saw a policeman acting like that.

We used to be allowed to call up people if they asked us to, and they were charged 6d a week to be collected and shared twice a year, we had to call on them on Saturday nights for the money and ask for any outstanding 6d that might be owing. I never liked that job and after a rush to get to the houses before they went to bed to be told to call again next week just about did it for me. Some locals like Folkestone Road might have one at 4am Manor Road, 4.15 Malvern Hill, 4.30 Kitchener Road perhaps two or three at the same time at the extremes of the beat, it was no joke whatever the weather racing to and fro, and then the best of it was, those who never did any night duty or were always put where there were no calls, all shared equally with those that did the work. It was shared at midsummer and Xmas and the few shillings came in very useful. If anyone wanted a single call that was 2d and not paid in. Mr Prescott, Magistrate, Shipping Agent, Short Street occasionally wanted a call when going to London, he told you to hold out your helmet and he would drop a shilling into it from the window, but such calls were few and far between. Any

[section 004] [page XXII] sum received as a gratuity exceeding 1/- had to be reported with the name and address of the giver and it was at the Chief’s discretion whether you were allowed to keep it, or if it should go into the Police Funds.

I was for about 24 hours beyond the dreams of Avarice with 80,000 Golden sovereigns to myself. It was a very cold wintry afternoon when I went to the Police Station dressed rough and with a weighted stick, in plain clothes to continue a watching job at River Without, lying up in a hedge. The chief, Mr Knott, called me to his office and told me he wanted me to go to the Prince of Wales Pier where on the station at the end I would see an Agent who knew I would be there about 4.15 or before and would show me some boxes of bullion that was to go on the S S Patricia to USA but she was a bit late. He would be down again before the ship got alongside, there were arrangements that no one should be allowed on the Pier and there were no boats alongside of any description. He had another man with him so I asked where the gold was, he said ‘under that tarpaulin behind you’, the tarpaulin looked rough as if it had been thrown there in a heap, nothing to show there was anything beneath. It was almost dark but I told him I must count the boxes before accepting responsibility as I should be entirely by myself. I counted 16 boxes, 5,000 in each, covered them again roughly and they went saying they [page XXIII] did not think she (the vessel) would be long, and they would be back.

I had brought no food or drink, it came on to snow and I was frozen to the marrow. I saw the glare of a house on fire (in Folkestone Road it turned out) but daylight came but no vessel or the agent appeared, till about 10am when he (the Agent) arrived with the Buffet Keeper from the Lord Warden Hotel. I told him I was frozen and starving and he said would I have some coffee. I said ‘if you’ve got any whisky give me a good dose and then some more in hot coffee, also a good feed of some thing or other’. I had a real good drink and then some more in hot coffee, half a chicken and some ham and bread. I told him I was prepared to stay for a bit longer if he would telephone the Chief to let him know and get a message to my wife to tell her not to worry. I stayed till after 4pm and as the Patricia had broken down in the North Sea and not likely to arrive, a gang of shore-force men with one of the long barrows with wheels like a cart that they used for mails and baggage were sent from the Admiralty Pier at the request of the Agent. They loaded the 16 cases into the barrow and with me looking more like a tramp than anything in charge, it was run to the National Provincial Bank, New Bridge. The Bank was opened by the manager and his staff to see it brought in to the strong room, I remained outside. The bullion next day was sent to Southampton to go by another vessel. When it was all over 10/- was handed to me at the Police Office for my duty, [page XXIV] I would willingly have paid that if I had it for a cup of hot tea that night.

Another very cold job I had was after PC Southey had been seriously assaulted and injured by a suspected poacher on Old Park Hill, I was Night Duty in uniform but was ordered on duty at 4pm in plain clothes, told to watch myself but at all costs to arrest the wanted man, who was a powerful and dangerous man to tackle. In the tussle he had left his cap behind and it was suspected he would go to his lodging during the hours of darkness to get some clothing before leaving this area. He had been lodging at Hillside. Snow was on the ground which on the grass at the back of Hillside had partly thawed and then frozen again so that it crackled like glass when walked on. It was difficult to secrete oneself as there was little to hide behind and I had to arrange the best position as he might enter from the front, but I thought the back being open to the hills was the more likely way. I was there as soon as it got dark but could not move about owing to the crackling underfoot and I stuck it till about 11.45 pm without result. My feet were practically dead and although I managed to walk I could not feel that my feet touched the ground. What a condition if he had returned (unless he ran away when he saw someone about, he could have treated me worse than Southey). When I got to the tunnel under the railway. Crabble Arch, my feet began to hurt and I had to stop. It was agony and I thought I should never walk again, but I kept lifting one foot after another and eventually I managed to get [page XXV] going again. It took quite a long time before I felt safe to step out, and when I reached home about 1am I had a slightly warm footbath and added a little more hot water at the tiume to get them warmed up before going to bed. I had never had such cold feet before, or since. The culprit was some months later arrested on a Warrant, brought back and dealt with.

I was very fortunate with anything that happened, but I must admit I did not neglect my duty, and the jobs did not just roll my way. I worked with a purpose, and that was why I liked night duty. If anything happened I was free to try whatever I thought, to deal successfully with the matter, not have to hand over a good job after you had brought it near success to somebody else and they take the credit. I could quote you some things that were no credit to those in charge, simply I had to pass on what I knew for the favoured ones to take on. It was heartbreaking to get brought out in plain clothes after they had had a day, perhaps two on a job and to be told you will go with — and if you get anything hand it over for him to take. The individual concerned had no heart for tackling anything by himself or the common sense or shrewdness for the job.

Here’s a case no one could take away from me. One early morning I was on the Sea Front, it was summer-time and daylight, when Sergeant Maxted came and asked if I had seen anyone about as someone had tried to break in at No 3? The Paddock and had broken a table knife leaving half the blade inside, but had failed to gain entry. The noise had roused the occupiers who saw a man he could not [page XXVI] give any description up at all, he could only say it was a man. I kept my eyes open and was extra busy till 6am but saw no strangers or anyone I could question. I left duty and caught the 6.5 tram to Maxton. PC Beer and PC C Cadman were also in the tram. I think it was about the first night of Cadman being a PC. We spoke about no one having seen anything of anyone being about, and as we got further on the conversation flagged. As the tram was passing Belgrave Gardens it passed a man going towards Maxton, I knew that was the man wanted. He was a stranger to me but I was positive (I have had several similar intuitions in my time and they were always right). I said to the other two who were sitting opposite, There’s our Burglar (and I being the oldest constable said to Beer: ‘Come on I shall want you when the tram stops’, which it was about to do. Cadman said: ‘me, as well’. I said ‘No, you can go home and get some sleep’. Beer did not seem to think much of it so I told him ‘whatever happens, if I’m wrong I take all the blame, if not you have half the credit’. We went back and I know Beer thought I was making a mistake or acting quite daft. When I met him I wished him a cheery good morning and asked where he was off to so early. He replied ‘I thought a nice walk would do me good’. I then asked where he had stayed or was staying in the town, and he said ‘the truth is I came into the town late and as it was such a nice night I thought a few hours on the [page XXVII] promenade till daylight would be better than taking a bedroom for an hour or two’. I had noticed some dried grass adhering to his coat and as I had been on the Sea Front all night I knew he was lying. I told him I was not satisfied with what he said and asked what he had about him and made as if to search him, he said, ‘Oh No’: I said ‘you can come round the corner or go to the Police Station because I intend seeing what you have about you’. He got on the high horse saying he would take some action against me if I did not let him pass at once and that I had no power to subject him to such treatment. I nodded to Beer to fall in behind as I did not know if he might drop anything although nothing had been reported stolen. I told him to settle any dispute I was taking him to the Police Station.

When we got in view of the Griffin PH someone came out and the prisoner said:- ‘Is that a Public House Open’. I said ‘Yes’, and he asked to go and have a drink. I said ‘if what you say is correct you can have a drink with me when we leave the Police Station, not now’. He turned sideways and said ‘It’s a — good job you’ve got a mate or you would know all about it’. I said threats won’t hurt me. When I went in the station the door was swung to and PC Smithers who was in charge came and asked what I had got. I told him I had brought him in on suspicion of being concerned in the Paddock job. He said ‘there’s nothing stolen, you can’t bring people in like this’, I [page XXVII note 2 pages with this number] said ‘I have done’ and turned to start a search. The prisoner at once raised his arms (so I knew he had been in before) and said as I went to feel inside his breast pocket, ‘be careful how you put your hand in there’, and the first thing I brought out was a broken table knife, half the maker’s name on it, the broken piece from the Paddock was produced and that had the other half of the name. There was a bit of excited feeling, so I continued my search and under his vest wrapped around his chest was wide strips of a damask tablecloth binding to his undershirt silver spoons and forks, also knives and ladles (it turned out later to be the whole contents of a Plate Basket) there were sets of each and by the time I had cleared them up he looked much slimmer.

Smithers rang up the CC D Fox who at once came over in his slippers and he was delighted, asked if I had charged him, had I any idea where the stuff came from, how did I know him, what was Beer waiting for. He sent Beer home but I said I must stay until something happened. He was charged with stealing from some person or persons at present unknown and put back. About 7.30 a young servant girl came running in saying all their silver was gone, somebody had broken in at 18 Victoria Park. She was brought round into the office and she was pleased when she saw and recognised the stuff as that stolen. She was told to ask her master to come down and prefer the charge. He went [page XXVIII] to Quarter Sessions, had two 18 month sentences, I was commended and rewarded by the Watch Committee and I afterwards went to Guilford Assizes to prove previous convictions, he got 3 years for burglary. His name was Chapman and as he passed with Warders in a Gate [?] he recognised me and shouted out “Hello Baker” and smiled.

I cut up old motor tyres and stripped the canvas to one thickness and so wore I believe the first rubber soled boots for night duty, they were very heavy but I could not hear myself walk and that was all that mattered. I don’t like recording it but some of my colleagues always seemed to wear extra heavy boots at night, so that if anyone was about they could get away unquestioned, their nerves seemed poor, one man when I silently showed up would always say with a sneer “seen anything, heard anything”, it showed they had a liking for their own footsteps because later on all men were issued with a pair of I think “Phillips” Rubber Heels and told they were to last six weeks. How they managed it I don’t know because with fair weather they would last me double that time but some of them were walking noisily on the plates in about three weeks. A few dry leaves on an Autumn night skidding along the pavement would keep them looking behind. I can’t vouch for the following but I believe t’s true. One extra highly strung was passing in the early hours through Dieu Stone Lane and another “to give him a fright” who knew of it secreted himself and threw in the air an electric light bulb which fell just behind No 1 and exploded with a bang. [page XXIX] No 1 never even looked round but cleared out as fast as he could go, he never reported anything unusual, then, or at any other time. Good man [underlined in text].

Another time I went about 2-2.30am through the path between the Park and St Mary’s Cemetery and saw waiting in the road by Charlton Cemetery Gates another PC who said “Coming up” meaning for me to accompany him up Chalky Lane and The Roman Road. I said:- ‘Not me, I go there as I should when on that beat but I’ve got my own beat to attend to’, he said:- ‘if you don’t, I shan’t go by myself and didn’t’. He was later made a Sergeant.

When Lord Kitchener, “Sirdar of Egypt” returned he landed at Admiralty Pier. The Force were paraded in top coats and marched to the entrance and between there and the Lord Warden Hotel stood on Parade for Inspection (I have a photo of it). I had heard he had steely blue eyes so I took notice and saw he had piercing blue eyes, never seen eyes more penetrating.

When the dowager Empress of Russia made her first visit, I was in plain clothes on the top promenade with instructions to see that no one overlooked the pier and boat (the pier was quite a narrow affair the same as when Lord Kitchener arrived). Journalists came from London but as they left the train were escorted off the Pier where they hung about so I kept near the steps at the land end. One asked if I would press a button on a circular arrangement on a tiny camera as she came over the gangway, he would be pleased to give £3 for a picture. I cleared him out, but the picture was published next day so someone had done it. She had travelled to Calais in a bomb proof [page XXX] train as she was so afraid of Nihilists. For bodyguard she had a huge Russian with full beard, wearing a rather tall Astrakhan hat like a silk hat without the brim, the whole railway was extra closely guarded with platelayers about every 100 yards to London as well as the Police at all bridges and crossings, but on her next visit the precautions were only the same as for other Royalty.

When King Edward VII on one occasion was coming over, he was to have a dirigible escort, the first to be in service, as well as destroyers. It was well advertised and folks flocked in from all parts to see the new invention, many undesirables from London were stopped at the Harbour Station by Scotland Yard Men (who had arrived early for that purpose) and sent back by the next train as suspected persons. When the dirigible was overhead people were craning their necks, using glasses, and leaning backwards to get a good view. When it was passed and folks felt for their watches they found someone had had a field day, nothing easier for a pickpocket, with everybody sticking themselves out and leaning backward.

A retired Chief Insurance Agent has his gold presentation watch and chain lifted and was grieved that in no way was it ever returned to him. Many others lost theirs but the culprits got away with it all. It usually happened that if anything of importance was advertised by the Railway Company, we would get an influx of undesirables who would be gone before householders returned home and found their house burgled. [page XXXI]

I remember one occasion when there were six, all a long way from each other, I had to go to Captain Jupp’s, Westband Gardens, Nr Shakespeare Road. The front door had been burst by bodily pressure, the iron socket for the latch broken and lay at the end of the Hall at the bottom of the stairs. Every Wardrobe and Drawer had been forced with a jemmy the mirrors in the wardrobes split by the pressure of the jemmy and all locks forced out, on top of the bed was a heap of jewellery and Indian filigree silver ware where it looked as if the whole of what they found had been tipped out and what they wanted sorted out and taken. Mrs Jupp and her sister Miss Erith had had golden guineas, (I don’t know now whether one, or how many) that their father had given them, they were gone. The damage was very heavy as all the articles smashed open were good quality. Moral:- Leave everything undone or open.

When the Dover Pageant opened (owing to thefts from the clothing of those taking part during the practices) which they were acting in their various episodes, I was told not to go near the Police Station but to go to an attic in Effingham Street where, (at the time I was told to attend), I should find one of Clarkson’s men to disguise me and show me how to do it myself as their staff would be busy all the week. With wig beard and dress I did not know myself, one man only recognised me by my voice, I told him not to mention it to others as I was there for a purpose, and although he saw me often enough he never [page XXXII] spoke. The thieves or some of them were told to return their clothes and they never asked why. They had fountain pens, money, wallets etc but it was not desirable to prosecute, one of them was a shady shopkeeper dressed as a Monk. My biggest difficulty was when my episode was on I might be seen around dressing rooms and marquees and so cause comment and perhaps suspicion.

Another time we had a series of thefts from Gas-meters from houses with a semi-basement where the coal cellar was under the front door steps, the doors of which, if locked, were broken open, but usually they were left undone. There was only one person who had seen anyone about and that was a neighbour of mine, Mrs Fagg, who was opening her lower door, saw and spoke to him, he saying he was looking for somebody, she did not know till the morning her meter had been robbed. She of course did not know of the robberies all over the town.

At the same time we were getting burglaries, but usually in the late evenings, so it was difficult to pick up anyone as folks were still about in the roads and streets. It got very bad, every day something or other so I asked Mrs Fagg for a fuller description if possible but she could not help. I said:- ‘Do you think if you saw him again you would know him’ and she said “yes” and ‘especially if I heard him speak, I feel sure I should know him’. Then I saw Mr Fagg and in his presence asked if she with her husband’s consent, that is, if he would give it, would consider [page XXXIII] coming out with me for an evening or two’s stroll in the hope that we should meet him, that was of course, subject to the CC [Chief Constable?] agreeing to the arrangement, they both agreed, and when I spoke to the CC he was not much impressed by the idea but something had got to be done, especially as the Inspector’s house had been entered, the Sunday joint pinched and his dog shut up, and a Metropolitan Policeman had had his marble clock and a mackintosh stolen from Malmains Road. So that night I took Mrs Fagg and wandered off up Frith Road as if it might be a courting couple. As we turned into Barton Road I saw a man by the gates of Clarks Nursery coming towards Frith Road and expected him to cross over so slowed up a bit so that I could meet and see his face, but he kept along by the school wall until I knew he could pass without me getting a good look at him and then he started to cross the road. He had no overcoat although it was cold. I said to Mrs Fagg ‘what about it, do you think that looks anything like him because I’m taking no chances’. She was hesitant, so I said ‘you follow up, I must catch him’. I ran through Avenue Road and saw him walking briskly on the opposite side of the road so ran and overtook him, apologised and said ‘a lady friend of mine wants to see you, you are Mr Friend aren’t you’, he said ‘No, she’s mistaken’, by this time Mrs Fagg had arrived and I looked at her, she nodded her head and said ‘No’. I then told him I was a constable and in answer to queries he said he was living at No – New Street, at present unemployed, was expecting to get a start etc etc. I wished him Goodnight and Goodluck and had no grounds to [page XXXIV] detain him as Mrs Fagg said he was not the man and there was no one else could identify him, but I knew, knew he was the man I wanted. I told Sergeant Palmer (Station Sergeant) what I had done and he said ‘you’ll be getting yourself into serious trouble if you’re not careful, fancy pulling a man up like that, you know nothing of him’. I said ‘No Sergeant, but I am willing to learn’. I had several skits from others about it, but I knew he was the man, no one else in the Force had seen him and I intended to make other enquiries and hoped they would lead to something definite.

I turned out in my own time next morning and went to the address in New Street, had an excuse if he happened to be in, but he wasn’t. I knew the landlady who was prepared to be helpful and she told me he had been staying there for two or three weeks, or more, but frequently was out all night and perhaps a night or two at a time. I asked if he had got anything in his bedrioom I could look over, she said:- He didn’t have a bedroom he sleeps on the sofa here in the front room and if the door is locked he don’t call me up but gets in the window. I had a look round the front room and told her if he enquired to say no one had called. I was more sure than ever now, the jobs continued and a quantity of silver-ware was stolen from the top of Priory Hill. Some began to try to take me out for a walk, saying, ‘Why don’t you catch him etc’.

It went on till I think Whit Monday, (it may have been Easter Monday) I was out in my own time and went opposite Waterloo Crescent as a Band was playing there to scrutinise those standing about. I did not [page XXXV] see him but he told me afterwards he saw me as he knew by seeing me about at so many different times I was after him he cleared out. That night at either Ramsgate or Margate an Inspector and Sergeant were talking when they spoke to a passer-by who said he was looking for lodgings, a constable joined them and then left as the passer-by was walking away, he then spoke to him and having knowledge of some minor offences during the evening and articles missing he took him to the Police Station to satisfy himself, he found the missing articles on the man, he (the man) said he had been unlucky in failing to make sure of a lodging, there was no credit to them as he knew he would have the rule run over him sometime during the night and if he gave his Dover address enquiries would be made, he said ‘the credit is Bakers, he’s the only one of the force knows me and I have been dodging him for weeks, he’s been after me at all hours and I’ve had several narrow shaves, he nearly had me this morning on the Sea Front, that’s how I came here and got stranded tonight’.

They brought him back, I saw him in the Reserve Room and he said he wished he had admitted it when I first stopped him, asked about the Leg of Mutton, he said the dog “supposed to be a good house dog” did not make any noise so he shut him up. The clock he had under his arm with the mackintosh over it when he walked down Folkestone Road and wished a Policeman outside the Engineer PH Goodnight. The silver from Priory Hill he dropped in the harbour in a bag behind the gates of the Granville Dock as he was afraid to sell it. A diver retrieved them flattened out where the [page XXXVI] gates had crushed them to the wall. He had been living with a woman at the Pier and had only used New Street when he thought it unsafe to go down there owing to it being late and the fear of being stopped and questioned. I was not mentioned or allowed in Court. Mrs Fagg afterwards told me she knew him when I stopped him in Frith Road, but she felt so sorry for him and the prospects of him going to prison that she denied all knowledge of him hoping he would go away somewhere else. The woman was also charged but was allowed to go.

His name was Mort and after coming out he got a job as Head Porter at the door of a London Hotel, he came to Dover and I saw him, I think he was killed in the 1914-18 War as he was a Reservist and I have never seen him since.

Another experience was with G Greenland. A message from the Metropolitan Police giving the names of two men and a woman named “Daldry” for stealing Bank-notes believed left for Australia by the SS Vallerat from Tilbury. Warrant applied for, Please Arrest. It was the latter part of the afternoon and I said to Greenland, the best thing is to ask the Shipping Agents what time such a vessel left because we have no warrant, even if they say “Arrest” and wire back. He said ‘its risky, if the Captain won’t let us have them, that is if we can catch the ship and they are aboard it’. I said ‘lets go to Crundalls Shipping Office’ and we did, there was no ship of that name, no doubt it was a mistake as the “Ballerat” was due to sail from Tilbury but he expected it had passed here by that time. We hurried off to the Sea Front and told Mr Brockman, boatman, we wanted to get [page XXXVII] in touch with the vessel, he spoke to someone else and then said he thought it had passed about half an hour before. We said if we could afford it we would hire his boat but we had no authority to spend any money, but if he would take us we would pay for the petrol, and if successful he would be able to claim all his expenses and a bit over. He told us he liked a “sporting” chance, rowed us to the motor boat and off we went out of the Western [harbour] entrance, there was a big ship going down the channel and he said ‘I reckon that’s it, we can’t catch up with that’. It was getting dark and the sea was none too smooth, the boat stood up on end at times so he made for the Eastern entrance, as we got just inside we were hailed by another motor boat lying alongside the steps and in reply to our query they said they were waiting to land the Pilot from the SS Ballerat, so with their permission we were transhipped to wait.

After a long time a flare was burned to the East and was answered from our boat and off we went to sea again. There was a heavy swell and I was told to stand on the cover of the bows and as we ran alongside, when the ladder came to near the boat I must jump on it because if the pilot started first we should never get aboard. It looked I thought like I should fall in but I caught the ladder and those behind shouted get on it, I did manage it but how I don’t know. I had never been on such a thing before and when I looked up it looked like climbing up the [castle] Keep. Anyway Greenland had a job to do it as well, so very carefully making sure [page XXXVIII] as well as I could I started climbing, it seemed never-ending till I felt someone take hold of my collar and then I was on deck, Greenland was soon up and he told the officer we were Police Officers, and did not disclose our business as there were quite a number of men about. He took us with him and we saw the Captain and stated our business, he at once asked if we had a Warrant. I said:- ‘Oh yes’, and made to feel in my inside pocket, he was not pleased but sent for the steward to bring him the Passenger List, ordered the boat to stand off, and the List having arrived the steward looked for the Daldry’s name and found it. He gave instructions to the boat “as he would not stop his ship” to be ready when he returned as he was going to take a round turn. (He had already been delayed truing his compass) He told us to hurry up and we were taken to the mens sleeping quarters after ascertaining the numbers of their bunks, the first one with a number we wanted was vacant and I thought they had been told we were aboard, just then a voice asked what was the matter and as I looked to his bunk I saw the number, one of those wanted “Greenland had gone I think to start a hunt” so I challenged him and he admitted he was J Daldry and pointed to another bunk saying his brother was asleep. Greenland came back and told me he would see about them and I could go and get the woman. The stewardess had been sent for but I was shown the woman’s quarters and right opposite the entrance was a curtained off bunk with the [page XXXIX] number I wanted, I saw that the curtain was a trifle bulged so spoke at the same time touching the curtain and asked her name, she replied Daldry. I asked her Christian name and she said ‘Ada’, I hung on for a bit waiting for the stewardess, and when she came I said ‘you must get up Mrs Daldry as I am taking you into custody concerned with your husband and brother-in-law in stealing the Banknotes’. She said ‘where are we’, and when I said Dover , she said they were not going to stop till they got to Las Palmas. She was hurriedly dressed while I waited in the gangway, when she showed up she was quite a girl, and only recently married, she carried a Mac, Book and Vanity Bag. I put my hand out and she gave me the Book, and then the Mac, but said ‘its only my vanity bag’, and expected to be allowed to keep it, but I said ‘I must have it’. She demurred but afterwards did let me have it saying:- ‘You’ve got it all in there’. Then we soon got ready to get down to the boat which came alongside.

Greenland went first followed by a seaman to safeguard one of the Daldrys, and all three went down the same way, with someone to help keep them from falling. I was asked if I wanted someone to help me, I said ‘I got up I shall get down, Thanks’. I wish I hadn’t said that, after a precarious descent, I heard someone tell me to jump, but it wasn’t so easy, sometimes the boat nearly touched me and then it was a long way below, it had got much rougher, I did at last make a successful jump. The prisoner’s luggage would be [page XL] sent back from Las Palmas, so they landed in tropical kit with three deck chairs, no luggage and only a handbag, they were all very sick as the motor-boat tossed about so and we were landed at the steps at the dump head of the Granville Dock. It was 2.0 am when we arrived at the Town Hall. The CC Mr Knott was waiting in the High Street for us and was glad because he had had no word of us, and Brockman had not thought to let anyone know. All he (the CC) knew was we had the information and as Offices were shut did not think it any use to enquire, expecting us to turn up sometime but when it came late in the evening he began to wonder and would not go to bed till he knew what had become of us. He did not grumble but thought we should have got in touch with the station, and we of course could only say that we never dreamt of being hanging about so long before seeing the ship and getting aboard, there was no way to let them know, in fact we never troubled about that, all we wanted was to make sure if possible of the arrest. We had a nice letter of commendation from the Commissioner of Metropolitan Police.

Sequel: Somewhere about 1926 I was sitting in the office when someone called, and when the Station Sergeant went to the wicket I heard someone say: We wondered if you would let us see the little room where we were kept after being arrested at sea on such and such a date. I recognised the woman’s voice so butted in with “How are you Mrs Daldry” and went to the wicket, her husband [page XLI] was with her and they were pleased saying they did not expect to see me when they called and what a memory I had to remember her voice. I asked about the brother and they said he was killed in the 1914-18 War. I had them round in the office and we had a real good chin-wag. They told me none of them had imprisonment and the notes belonged to a near relative. I cannot remember how it was that they got away with it.

Somewhere about this time I was for Watch Committee Parade and for some reason had to go down town and got rather behind, so on my way home I called in the Barber’s shop next the Alma PH for a quick shave, a thing I rarely did as I always shaved myself. There was a man in the chair so I made to leave but the barber said I shall not be long, so I stayed, not because of what he said but I had that intuition again. I looked at but could not recognise the man in the chair as answering any description of wanted persons but I knew and began to think and worry as to who he might be. He was finished and the barber said “Next” but I looked at the man and followed him outside and took a chance shot. I said, ‘Hello, how long ago when you left Ramsgate’. He replied ‘Are you a copper’ and I said “Yes”, he said what do you want? That Watch and I said “Yes”. He handed me a mans watch and I took him to the Police Station, on the way he said ‘Are they putting anything else up against me’ and I said ‘No to my knowledge’. Which was true at that time, but he was wanted at [page XLII] several places.

Now here is the most puzzling thing of all. One night I was on No 9 Beat that included Military Hill to Mount Pleasant to Cowgate Hill, to King Street and back to the Station. Jack Groombridge was a Corporal (we had corporals in those days), to be acting Sergeant if necessary, and as we had our Night Sergeant, he was on duty with the Fire Escape in the Market. I had left him somewhere just before 1.0 am and was trying my fastenings and had nearly reached the Metropole Hotel when I had an intuition there was someone about, who knew I was about, and I knew I had been close to him. I went back slowly to the corner of the Market and saw Groombridge in the Walmer Castle PH doorway looking towards Cannon Street. He started to walk to me and I to him, he thinking I had found some premises insecure. I said:- have you seen anyone about, that tickled him and he began to rag me about seeing things. Then I knew where the fellow was and told him there was someone in the butchers shop next to Highleys. He thought that a proper joke, but as he was a Corporal and that shop was on another beat I could not go there, but he could (if there had been no Corporal I should have gone myself). He went to the door, tried it, laughed, and said it was my imagination. I said All Right, but if I were you I should keep my eye on Highleys. The next time I went round Groombridge was in a sweat and said “he was standing in the Walmer Castle doorway about half an hour before when he saw a [section 007] [page XLIII] man suddenly dart noiselessly from the butcher’s doorway, he ran to Market Street as that was the way he went but could neither see or hear anything of him. He har tried the door but it was still locked. I had a look and then saw an iron bar one of three or four over the fanlight was loose at one end. He begged me not to say nothing about it. Next night on Parade we were asked if anyone saw anyone about during the night as the desk at the butcher’s shop had been broken open, a small sum stolen and an iron bar wrenched away from over the door. How did I know? Groombridge never after queried anything I did.

When the tram-road was laid to River the road was excavated on the near side as far as Crabble Road to allow for the foundations for the rails. I was on Point Duty or it might be almost called a patrol because there was such a long stretch open at the time and I had to do the best I could by myself. There was only room for one line of traffic from Manger’s Lane or just above it to the junction with Crabble Road. I let through a line of several pair horse vans with the Sunday School children from St Marys who were going to a School-treat somewhere in the Kearsney Area. A motor-car quite a rarity arrived coming down the hill but it had to stop, the engine was left running to make sure it would start again and I put my arms up to stop any further traffic from coming up and as the vans of children were nearing the junction I went towards the car intimating he could proceed as soon as they had passed, as the last van with two powerful shire horses [page XLIV] was approaching the driver of the car started the car up, Chug, Bang, Chug, Bang and increased the noise so much it frightened the horses who suddenly swerved and turned to come down the hill the driver had fallen backwards among the children and they started to scream, further frightening the horses. I had gone part of the way down the hill so as to stop anything coming up and on turning having heard the screaming saw the van would soon have the two wheels in the excavation. How I reached and stopped them I don’t remember. “I had been used to horses” but I found myself on the pole between the horses, they were terrified but as I gathered and pulled the reins to head them away from the trench, the driver managed to get on his seat and I handed the reins back to him. The horses were soon pacified and pulled up and the van followed up the hill as soon as the traffic allowed. I had such a lot of money given me that I felt embarrassed and as I had not time to ask names owing to attending the traffic, I decided not to say anything about it, it was nearly all half-crowns and I don’t know how much I had.

About 4.0 pm Sergeant Figg came up, I reported ‘All Right Sergean’t, he said “All Right”, stood there for a bit and said any Reports. I said ‘No Sergeant’. Then he started spluttering. ‘Have you had any runaway horses’. I said ‘Yes, but they didn’t get far’. ‘Give me the report’ he said. I said ‘I can’t leave a job like this to make a report and I have taken no names or any [page XLV] particulars’. He said ‘I’ve been sent to take this job on whilst you go to the Police Office, The Chief wants you, and don’t be too long, I don’t want this job as I’ve other things to attend to, so get back as soon as you can’. I expect he was extra thirsty as it was a hot day. As soon as I got to the station I was taken to the CC’s office and instead of a wigging, he was jubilant and all smiles. He didn’t keep me in doubt, “again what have you done” he said. ‘People have been ringing me up about you and saving that van of children from being tipped over into the trench, tell me how you got on the pole’, all I could say was “I don’t know myself” then he said ‘I have also had several gifts of money from different people sent in for you, and am having letters appropriately worded, and copies for your perusal and signature will be sent to each’. He handed me quite a nice sum and then I said that I also had money pushed on me but did not know from whom so could not give the names in my report. He asked ‘how much’ and I was going to turn out my pocket when he said ‘Never mind, you ought to have obtained their names, but as you haven’t, don’t mention the money’, so he never knew what I did have. Letters were also sent in and I was taken to the Watch Committee, Commended and Rewarded. My house I had rented from Mr Boyton, Junior and his sister was in the van as the one in charge. He came up to the house to thank me personally and said he would like to do something for me, wouldn’t I like to buy the house out of my rent, he could arrange everything if I could add [page XLVI] another shilling a week to my rent. That’s how I started to buy No 45, it was a long uphill job which seemed endless but eventually I carried home the Deeds. We had managed it, but not without effort.

Owing to a lot of stealing of clothes from clothes-lines I was fetched out for plain clothes duty from 4-12 midnight. I had noticed that most of the offences were in the Folkestone Road area so at once made enquiries at Mount Pleasant from a friend and was assured nothing had been offered of the description given, and I also made enquiries at dealers, but found they were all wise to the thefts but they knew nothing. I went to the foot of the steps behind the Malvern PH so that I could see without being seen because I had a feeling it was a soldier. I went to the station at 10.0 pm and got chewed up for not reporting at 8 o clock but I was not wanted for anything. I was asked where I had been and when I told them only got a sneer and was told not to waste my time there again. Next evening I took another route and when I got in at 8.0 pm was told another lot had gone (from North Street). I made enquiries but no [one] had been seen only a soldier waiting about, supposedly for a girl, from that the enquiries went to the citadel and it was found clothing still damp had been sold by one of the men and parcels had been sent to his home at Chatham. The police there were informed and they recovered quite a lot of the articles and the soldier [page XLVII] was brought in. I had nothing to do with it, but if it had not been for me they would not have got anybody. All they thought about was visiting second-hand shops.

About this time also was brought in “The Black List”, “Habitual Drunkards” were on conviction photographed and with their descriptions printed and circulated to all Licensed Houses. The circulars had to be, and were hung up in a prominent position for all to see. The individual concerned was warned not to enter licensed premises and the licensee of any PH was held responsible to see that he did not do so. Should he attempt to obtain liqueur he should eject him and inform the police, should anyone obtain for him, or give him his own drink, that person would also be dealt with. We had quite a number of these circulars with photos exhibited in the whole of the Licensed Premises. It eventually became a dead letter.

I had a week of success in arresting Deserters, £4-10-0. The first one denied that he had ever been in the Service, I had a good talk with him and started walking with him saying that to make sure I would look at the Gazette again, and then should he be accosted again he could refer to it. I had intended making some excuse to avoid going to the station although he looked a smart disciplined man, as an ex-service man. He said:- ‘are you going to take me in’ and I replied:- ‘only to see the Gazette’. Then he said:- ‘That’s done me. I have been a deserter from the Navy for over a year. I shall have stoppages of pay for months, you will get £3 Reward and I shall have to pay all your expenses, as well as the Navy punishments. I have been afraid all the time of being arrested and am glad it’s all over’. I got the £3 later and took him to Chatham the following day. That was on a Sunday, on the Thursday following I met a man in Dieu Stone Lane and challenged him, after denial, he admitted being an Army Deserter, 10/-, and on the Sunday morning on Castle Hill met a young fellow carrying a rush basket, (the same as used for fish or poultry). He had a good blue suit and I thought he was from some institution. I asked what he had in the bag and found it was broken food, after much questioning he said he was a ships writer [shipwright?] from Chatham and had been away about eight days, as he did not like the navy. I took him back to Chatham after Court on Monday, £1. One man who was clerking and getting extra money for it, said, ‘I do all the work, what about it’. I put down 2/- and he took it. I knew he had had me before, so did not feel very generous.

I was on morning duty in Folkestone Road one bitter cold day in March, a canvas shelter in an iron tubing frame was in the road outside Belgrave Gardens as the joints of the tram-rails were being planed down level. I had just passed it and was passing the Girl’s Orphanage when I heard a horse coming from behind me at a terrific rate, and on turning saw an Army Horse with [page XLIX] the two front wheels of a gun-carriage attached, I could see that I would not be able to stop it as it was on slightly falling ground so blew my whistle to attract attention so that folks could get in front gardens or somewhere and just had time to clear myself. As it approached the rise to the Priory Bridge it was easily stopped but during that time I heard another run-a-way coming as its hooves sounded on the granite setts.